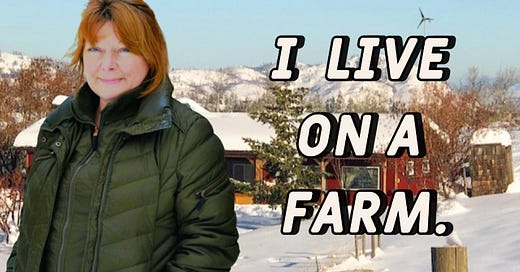

I live on a farm.

Did you ever experience a moment of surprise where you find yourself, almost suddenly, in a place or situation you never anticipated? A surreal revelation, there's a sense of being suddenly teleported from one way of life to another, as if no transition existed.

That was me, yesterday.

It was morning and I let the chickens out. I stood watching them peck about and stretch their wings. Occasionally, one would clumsily take flight and then, almost in a panic, land "Greatest American Hero style" near the others. They're only 10 weeks old so they're still figuring things out, too.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Good Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.