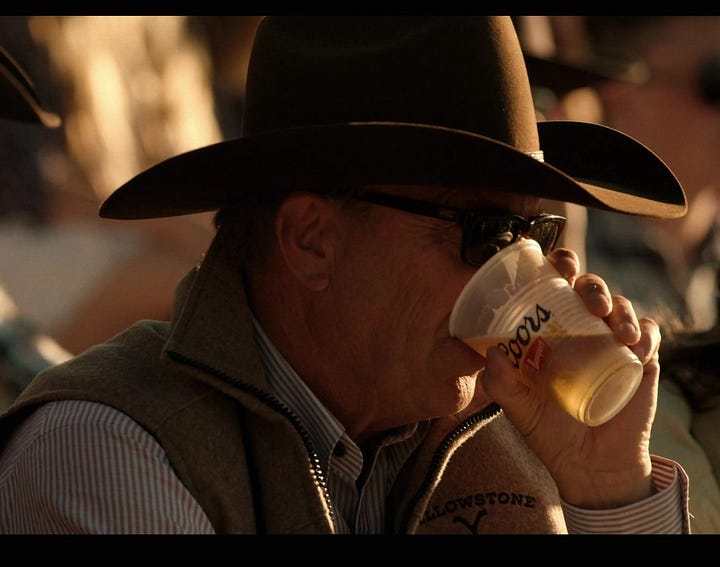

On a recent trip to the grocery store, John and I came across a large cardboard display just between the produce and beer aisles. In bold white type, the ad encouraged us to “Live Like a Dutton”.

Indeed.

If you haven’t seen the show this ad refers to, Yellowstone features a number of characters of spurious morality that are no monuments to justice, especially after they’ve been drinking. The Coors promotion seems like really bad advice, unless you’re looking to get branded on the chest with a hot iron or taken to the “train station”.

No thanks.

Nevertheless, every now and then as we’re working on the farm, dust stuck to our sweating faces and grit in our teeth, John and I stop to ask… Are you feeling like a Dutton yet?

Well, maybe like a Dutton ranch hand…

Most jobs around here are dirty jobs, varying only by degrees. So far in May, it seems we’ve both been using grime as our sunscreen as we work on fencing.

Recently, John and I raced against the clock to get an additional ring of fenc…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Good Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.