Water: A Desert's Gold

Most people seeking to live off grid aren't working with an unlimited budget. We're no different. When we chose our property, cost was a factor that influenced every other. It'd be heaven, no doubt, to live where the weather is always 70 degrees and sunny, where the fields are green and gold year-round. Those places are already full of people, for obvious reasons. They're also out of our budget.

Without disclosing our exact location (for reasons of privacy), our area is bountiful in the spring, but spring is a very short season. Actually, we have three seasons: frozen road season, muddy road season, and dusty road season. Currently, we're transitioning from frozen road into muddy road season and water is everywhere: thawing puddles of mud, hidden ice slicks in the shade, stubborn frozen snowbanks still 2ft deep... it's everywhere.

In just a few short months, all this glorious water will disappear - literally evaporate - amidst the dry heat of dusty road season. Coincidentally, that's when all our plants and crops will need it most, so we have to work for the gold of the desert: water.

Our home came with an existing 400ft well with a 12v pump hanging precariously off a garden hose 60ft down the hole. The well isn't the best producer anyway (1/16 gmp - yes, that's a trickle!), so the tiny pump dangling at 60ft wasn't doing much to help that.

And that's how we met Chester.

It takes some pretty heavy equipment and expertise to deal with wells - expertise we don't have - so in early fall 2020 we started calling around for someone to come look at our situation. After leaving many messages, John finally spoke with Chester - the one available well guy. He wasn't interested in coming out at all once he learned we were off grid. Unfortunately, Chester hadn't had the best experiences with "off grid" people. John's quite a charmer though so, after a bit, Chester agreed to come look at our well.

"What you've got yourself here is a dry hole."

Chester

Well, Chester's comments stoked my deepest fears: that the "great producing" well we were sold that had been enough for the family of five who lived here before us had, at last, dried up. Regardless, we decided to do the only thing we could do at the time and lower the pump.

Because the new solar system John installed would handle more power, we replaced the existing 12v pump with a 220v on pipe and lowered it to 380ft. That seemed to do the trick - or at least get us by.

The water pumps to a 1200-gallon storage tank buried in the hill above our house. Theoretically, the water would gravity down into the house, but that didn't produce enough pressure, so we installed a 24v DC booster pump in the cellar.

Because it is such a "dry hole" (thanks, Chester), we also installed a float controller to turn the well pump on and off automatically. In the event that the well water level is too low, you can burn out your pump if it stays on, pumping air. The float controller is a safety mechanism to prevent that and save your pump.

All of these improvements meant trenching to bury electrical cables in the ground. Since we had to rent a trencher anyway, while we were at it, we also trenched a line for power to the shed for the generator, a trench for power for the barn, and a 4' deep trench for a waterline to the future greenhouse site.

Wouldn't you know it, as soon as we got the trenches dug and the lines installed, it snowed and covered the trenches completely. So, from October to April 2021, we had to remember where the trenches were so we wouldn't fall in!

Now, back to the well... Because the only way to know the water level in the reserve tank buried in the hill was to open it and use a long stick, John installed a level gauge. He installed the gauge, as well as a tank vent, taller than the snow level in winter so we can read it easily year-round without opening the tank.

If you're wondering about cost, it was around $7K to buy a new well pump and have it lowered from 60ft to 380ft deep. Of course, that amount doesn't include the booster pump, gauges, and float controller that we added, or the trench rental and electrical supplies. It adds up, but since water is probably the most important resource we have, it's well worth it (no pun intended!).

Because our sad little well is such a low producer, we're on the list to have another well drilled this spring (2022). There's a $10K deposit just to get on the list to drill, and then there is no guarantee of finding water. There's a healthy grove of Aspens north of the house and that's a strong indicator of water but it still feels riskier than a Vegas roulette wheel.

After the new hole is drilled - assuming we strike gold - we still have to pay for a new pump, electrical and water lines, and trenching. We're estimating (hoping) for under $50K total and a great producing well - that'd be ideal! The saga continues this spring.

Plan B for Back-up: The property behind us is owned by a very kind and generous cattle rancher with a tremendous well. We allow his cattle to graze a good portion of our land and he's extended his well to us, should we ever need it. That's been a lifesaver a few times when we've needed to fill our reserve tank and our well wasn't "in the mood".

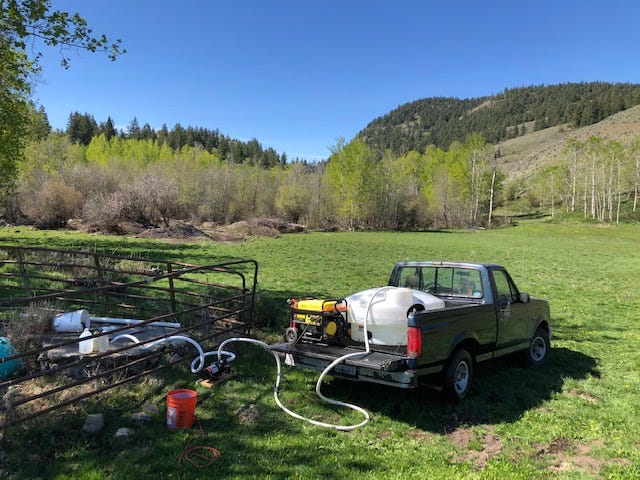

When this happens, John loads up our old Ford F150 (we call it "George") with a tank, pump, and portable generator and hauls water to our reserve tank on the hill. It takes about 6 loads to fill it.

Since our well is essentially a "dry hole" (I should probably quit dissing it, huh?), it doesn't provide enough water for the garden and greenhouse. Fortunately, we have one more source of water we use for irrigation.

Last summer, we bought the 20-acre parcel to the NW of ours; it has an existing 8ft deep well. There's no pump and it's too far from the house to run that much line but, fortunately, it's close enough to the greenhouse and high enough to use gravity. The well is at 3700ft elevation and 1800ft from the greenhouse so early last summer, we ran 1800ft of .060 irrigation pipe from that well to the greenhouse. Once we got the gravity feed going, it worked great - for a while.

Then, the water stopped. No pressure. Nothing. Where'd the water go?

John checked the well and, while it was low, it was still producing. Still no pressure on the line, though. He checked the line itself and - mystery solved - bite marks!

The line was punctured deeply by some large, thirsty animals seeking water in the heat of summer. When it's super-hot out and cool water is passing through the line, condensation can form on the outside of the line that attracts thirsty creatures. Now we know.

At first, we patched and taped the holes but it kept happening, so we replaced the entire 1800ft line. This time, we used SIDR 7 (standard inside dimension ratio .150) - the thickest service grade irrigation pipe you can get. If something bites through this line, we have bigger issues than water!

Over the past couple years, we've learned a lot from our water (mis)adventures. First of all, we've developed a genuine thankfulness for our "dry hole" of a well and its ability to meet our needs. We still do laundry; I use my clawfoot tub regularly; we wash dishes several times a day; we flush toilets - we do all the regular things most people do in their homes with water - but we're painfully conscious of every drop.

Since I remember taking very short (and sometimes cold) showers when we moved here in 2020, I now view my "serenity baths" as a luxury. Also, we never leave water running while we wash dishes or brush our teeth. It's just too precious. And, of course, there's the classic toilet mantra: "If it's brown, flush it down. If it's yellow, let it mellow." So, I guess things are a little different out here than in town, but maybe that's not such a bad thing. Even when we get our tremendously powerful gushing well this spring (fingers crossed), we'll continue to use water with gratitude and a conscious appreciation of its value.

Another thing we're learning is ingenuity. If one water source doesn't work, you find another - even if that means hauling and storing water. Or using gravity. We've recently begun diverting rainwater and snowmelt into a barrel to feed the underground tank that runs the downstairs toilet (natural plumbing).

I think the most difficult lesson for John has been the variability of nature (I'm assuming, but he'll tell me if I'm wrong). Nature moves at her own pace; water levels vary and there is nothing we can do about it but wait. For a man who excels at fixing problems, this kind of passive acceptance is difficult. Sometimes John will manually run the pump for 5 hours and the water level rises an inch; sometimes he runs it for an hour and the level goes up 5 inches. It all comes down to that waterhole and how much water has seeped through those invisible and mysterious underground channels.

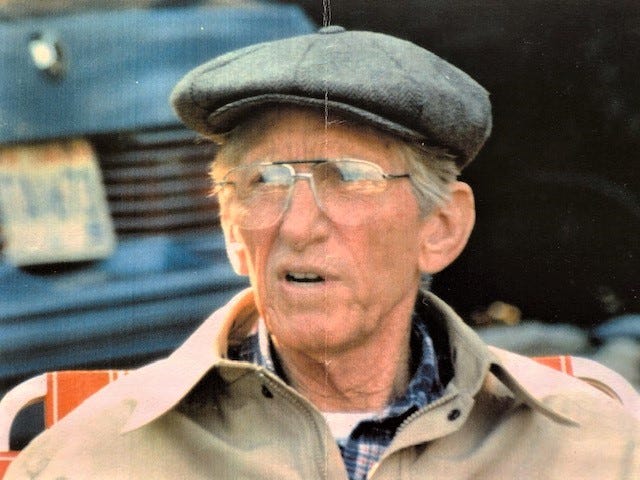

At times like this, I think about my grandfather who left the "insecurity and unpredictability" of the family farm for the overly hyped security of a textile mill. The idea of becoming part of a progressive system has been pushed for a long time. It's pushed as the responsible thing to do and most good people, wanting to do the right thing, fall for it. In his day, for him, security took the shape of a textile mill.

For those who aren't familiar, when mills were built a community of housing developed around the mill, also owned by the mill. These were called mill villages and the workers lived there (owners did not). Typically, there was a company store in the village and workers were issued credit to use there. It was very common for workers to become indebted to the store until, basically, they were working in the mill just to pay the store and their rent. Who hasn't heard "16 Tons" by Tennessee Ernie Ford?

"Saint Peter don't you call me 'cause I can't go, I owe my soul to the company store".

Tennessee Ernie Ford

At the time, the mills were pushed as a secure alternative to the variable nature of crop yield and property taxes. Many rural people gave up their land or left the family farm to explore urban opportunities and "get ahead". Fast forward to now: food is delivered via truck, water and power can be turned off from miles away at the flip of a switch, and rising property taxes are still a threat. More importantly, the source of that water, food, and power is completely out of our hands (most of us).

I think if my grandfather were alive today, he'd be pretty proud of what we're doing, living off grid. He wouldn't mind the inconveniences of hauling water on occasion or having to "let it mellow". He was very down to earth in that way. I think if he could see how the so-called security of city life had deteriorated people's actual life skills, he would have stayed on the family farm in protest.

In exchange for the work to obtain basic resources, there's a gift obtained: conscious awareness of every turn of the faucet and light left burning. Some would call that awareness an inconvenience, but I consider it a reminder of our bond to, and reliance on, the very land itself. When we stay connected and care for the land, it cares for us in return.